How Did The Early Methodists Handle Ordination and Succession?

Leadership succession in early Methodism was marked with a certain theological ambiguity, which stemmed from its founding father, John Wesley. Throughout his long life, he liked to consider himself a true son of the Anglican church, not the leader of a sect. As a true churchman, he believed there was divine merit in an apostolic succession, as it conveyed the historic commission of Jesus to Peter.

Wesley felt keenly the criticism that, in founding Methodism, he had stepped outside the Anglican branch of apostolic succession. He was also well aware that, having been only an Anglican priest and not a bishop, he could not himself ordain anyone to a higher office than that – but would need to in order to cover Methodism’s spread in two continents.

The matter came to a head with the arrival in England of Erasmus (Gerasimos), Orthodox bishop of Arcadia in Crete, who had been living in exile in Amsterdam. Wesley met him (conversing in Latin) and, as the Dictionary of Methodism states, ‘was tempted to see Erasmus as a providential means of obtaining ordination for some of his preachers.’ He had his preacher John Jones check Erasmus’s credentials with the Metropolitan (Archbishop) of Smyrna and he was satisfied.

Yet John and Charles Wesley quickly had misgivings, perhaps because of strict laws in England (statutes of Praemunire) forbidding any activity seen to promote foreign powers – represented by Erasmus. Against Charles’ advice, Jones was ordained by Erasmus at some date before March 1764. Some other Methodist preachers persuaded Erasmus to ordain them, without Wesley’s knowledge or consent.

This ushered in a time of confusion and accusation in the Methodist movement. Certain publications alleged that Wesley had bribed Erasmus to consecrate him as bishop, and Wesley had to defend himself: ‘I never entreated anything of Bishop Erasmus… I deny the fact.’ Wesley saw the need for caution, while re-evaluating his understanding of biblical ordination and his own empowerment to ordain. It would be 20 years before he consecrated Thomas Coke to be bishop of the Methodists in America.

At home, Wesley determined to appoint John Fletcher as his successor. Swiss by birth, Fletcher was an Anglican priest but became an ardent supporter of Methodism. From 1757 onwards, when Fletcher was 28, he became Wesley’s coadjutor. Wesley wrote in his journal: “Mr. Fletcher helped me again. How wonderful are the ways of God! When my bodily strength failed, He sent me help from the mountains of Switzerland; and a help meet for me in every respect: where could I have found such another?” Fletcher quickly became the most influential person in Methodism next to John and Charles Wesley.

Fletcher’s numerous writings clarified and synthesized Wesley’s developing ideas. Wesley said they frequently consulted one another on the most important issues and that their friendship was sealed with mutual loyalty. Wesley further said: “We were of one heart and one soul. We had no secrets between us for many years; we did not purposely hide anything from each other.” Wesley spoke of “the strongest ties” between them and wrote of Fletcher: One equal to him I have not known—one so inwardly and outwardly devoted to God. So blameless a character in every respect I have not found either in Europe or America; nor do I expect to find another this side of eternity.

In 1773, Wesley invited Fletcher to become his successor. He told him that he was the only person qualified to serve as his sole replacement, noting his popularity with the preachers and his “clear understanding…of the Methodist doctrine and discipline.” Fletcher did not think it was the proper time to take on this responsibility. He believed his continuing task was to write as an interpreter of Wesley’s theology. In 1776, Wesley repeated the invitation, adding: “Should we not discern the providential time?”

Again, Fletcher declined. He knew that he was in failing health. So Wesley decided on a different path of action. At the Methodist Conference of 1784 (Fletcher’s last before he died aged 55), Wesley announced that, for the British Isles at least, he would nominate 100 preachers to serve jointly as his successors. For America, being free of laws of Praemunire meant Thomas Coke could act appointed the great circuit rider, Francis Asbury, to succeed him as the head of transatlantic Methodism.

It is perhaps noteworthy that the handing on of the bible that Wesley used for field preaching became a traditional symbol of Methodist succession.

Disability Didn’t Stop 18 Year Old James Parnell, the first Quaker Martyr

Courageous faith isn’t just for special, brave people. Some of God’s heroes had to overcome serious limitations, even to get started. One such was James Parnell (1636-1655), from Retford in Nottinghamshire. He was a delicate lad, short for his age and sensitive. He loved Jesus and felt there must be more than going to the parish church.

In 1653, when he was 16, he heard of George Fox, the leader of the Quakers, who was in prison in Carlisle. Weak as he was, James walked the 150 miles and, fainting with exhaustion, was allowed to visit Fox. We have no record of their conversation, but Parnell was filled with the Holy Spirit and commissioned by Fox to be an evangelist.

He had just two years of life left, but they were amazingly fruitful. A colleague at the time, Stephen Crisp, subsequently wrote of him: ‘He was of a poor appearance, a mere youth, coming against giants; yet the wisdom of man was made to bow before the Spirit by which he spoke. He was a vessel of honour indeed and was mighty in the power and Spirit of Emanuel, breaking down and laying desolate many strongholds and towers of defence, in which the old deceiver had fortified himself with his children. Much might be spoken of this man, and a large testimony lives in my heart, to his blessed life, and to the power and wisdom that abounded in him.’

Disinherited and turned out of home by his parents, Parnell set about the work of the gospel. Sometimes with a partner, sometimes alone, he went from house to house, ‘preaching, praying, exhorting, and turning the minds of all sorts of people to the light of Jesus.’ He was ridiculed for his short stature, and often after preaching he was exhausted. Faith kept him going.

Hearing that two Quakers had been whipped at Cambridge, he went there and preached himself. Far from keeping a low profile, he published two tracts, against the corruption of the magistrates and of the priests. He was imprisoned until a court hearing, where the jury was unable to prove his authorship of the tracts. So Parnell was given a magistrates’ pass branding him “a rogue” and escorted out of the town by soldiers and a mob armed with staves.

He continued to preach in the area of Ely, Cambridgeshire. In a letter he records: “There is a pleasing people [congregation] arising out of Littleport. I remained there a sufficient time among them. There are about sixty people who meet together in that town alone.” He was often set upon by angry crowds. On one occasion, he records, “the power of God was wonderfully seen in delivering me, so that I can’t remember if they hit me.”

He continued in the east of England, strengthening existing Quaker assemblies and planting new ones at . Finally, Parnell was arrested after preaching (heckling) in St Nicholas’ Church in Colchester and accused of blasphemy. At his trial, he was acquitted of the most serious charge but fined £40, a hefty sum equivalent to c. 570 working days’ wage for a skilled labourer at that time. Parnell refused to pay.

So he was imprisoned, in a cell at Colchester Castle that can still be visited today. He was able to write letters, some of which have survived. “I am committed to be kept a prisoner, but I am the Lord’s free-man,” he wrote in one. In another, he counselled a recent convert to the Quaker message: ‘Lie down in the will of God, and wait on His teaching so that He may be your head. By such you will find the way to peace and dwell in unity with all the faithful; and though you are hated by the world, yet in God is peace and well-being.’

His jailers starved him for days at a time, then let him climb down a rope to get food. The jailer’s wife and daughter used to beat him, and on occasions he was locked outside in mid-winter. It was too much for his weak constitution. One day he had no strength left to climb the rope but fell to the concrete below, and died of his injuries. He was buried in an unmarked grave, the first of several hundred Quaker martyrs. He was just 18 years old. His message to all of us is summed up in the last words he sent to the Quaker believers in Essex: “Be willing that self shall suffer for the truth, and not the truth for self.”

Faith, Beer and Public Health: the Story of Arnold of Soissons

Arnold of Soissons (1040-1087) was a Belgian career soldier in the service of Henri I of France. At some point he experienced a religious awakening and joined the Benedictine abbey of St Medard at Soissons, France. Here he must have shown considerable potential, as he was made abbot in his thirties – a role of great responsibility. For a short time he was even bishop of Soissons, though against his will, and when an opportunity came, he withdrew and founded a new monastery at Oudenburg in Flanders.

The Benedictine order already had a long history of brewing beer. There were several reasons for this. The founder, Benedict of Nursia, stipulated in his early 6th century Rule for the life of monks that they should not live off charity but rather earn their own keep and donate to the poor by the work of their hands. So monasteries produced cheese, honey, beeswax, wool and much else, selling what they did not need themselves. Besides, they were to practise hospitality, so beer was available to serve to guests and pilgrims.

Another reason was the health-giving property of beer itself. It was cheaper than wine and could be produced in colder climates. It required water to be boiled before fermentation, making beer safer to drink than water, since drinking water at the time could be unsanitary and carry diseases. The beer normally consumed during the day at this time in Europe was called small beer, having a very low alcohol content, and containing spent yeast. The drinker had a safe source of hydration, plus a dose of B vitamins from the yeast. It has been estimated that the average monk drank more than 20 pints a week!

That’s where Arnold came in. He encouraged local peasants to drink beer instead of water. This meant more sales for the monastery, but it is likely he shared the recipe with them, for the sake of public health. And, when a cholera epidemic (spread by water) ravaged the region, the Oudenburg area stayed safe while thousands elsewhere died. On another occasion, he prayed to God to increase the beer supply of a monastery after part of its roof had collapsed and destroyed the majority of the barrels. The prayer was answered and the supply of beer supernaturally restored. A neat take on Christ’s miraculous multiplication of loaves and fish that fed the 5,000?

These (and other signs) were interpreted as miracles, and after his death he was quite rapidly canonised by the Roman Catholic Church. St. Arnold is traditionally depicted with a hop-pickers mashing rake in his hand, to identify him as patron saint of brewers. He is honoured in July with a parade in Brussels on the “Day of Beer.”

God’s ‘Wise Woman’? The Pipe-Smoking Prophetess who Enabled a Move of God in Cornwall

In my reading of Church history, I regularly find colourful characters who didn’t fit the usual pattern but whom God used in surprising ways. Perhaps it was always so? As early as Genesis 20, King Abimelech of Gerar talks with God and behaves uprightly, yet the patriarch Abraham cannot see the possibility of good in anyone in Gerar.

One of these “oddballs” – outsiders who were, in God’s view, very much “in” – was an unnamed woman from Cornwall, England, in the 1850s. We meet her in William Haslam’s autobiographical From Death Into Life (download free here). Haslam was greatly used by God in a revival in Cornwall, with many conversions and amendment of lives. Yet it almost never happened, because Haslam nearly died – but for the pipe-smoking prophetess. We read:

[There was] ‘a tall, gaunt, gypsy kind of woman, whom they called “the wise woman.” She had a marvellous gift of healing and other knowledge, which made people quite afraid of her. This woman took a great interest in me and my work, and often came to church and house meetings.

‘One day she visited the parsonage and said “Have you a lemon in the house?” I inquired and found that we had not. “Well then,” she said, “get one, and some honey and vinegar, and mix them all together. You will need it. Mind you do, now.” Then she put the bowl of her pipe into the kitchen fire and, having ignited the tobacco, went away smoking. The servants were much frightened by her manner.’

[Later that day, Haslam was caught in a thunderstorm and held house meetings in wet clothes all evening.]

‘At three o’clock in the morning I awoke, choking with a severe fit of bronchitis. I had to struggle for breath and life. After an hour or more of the most acute suffering, my dear wife remembered the lemon mixture, and called the servant to get up and bring it. It was just in time. I was black in the face with suffocation, but this compound relieved, and, in fact, restored me. I was greatly exhausted with the effort and struggle for life, and after two hours I fell asleep. I was able to rise in the morning, and breathe freely, though my chest was very sore.

‘After breakfast, the “wise woman” appeared outside the window of the drawing-room, where I was lying on the sofa. “Ah, my dear,” she said, “you were nearly gone at three o’clock this morning. I had a hard wrestle for you, sure enough. If you had not had that lemon, you know, you would have been a dead man by this time!”

‘That mysterious creature, what with her healing art, together with the prayer of faith and the marvellous foresight she had, was quite a terror to the people. One day she came, and bade me go to a man who was very worldly and careless, and tell him that he would die before Sunday. I said, “You go, if you have received the message.” She looked sternly at me, and said, “You go! That’s the message!” So I went. The man laughed at me, and said, “That old hag ought to be hanged.” I urged him to give his heart to God, and prayed with him, but to no effect. The following Saturday, coming home from market, he was thrown from his cart and killed.

‘She was not always a bird of evil omen, for sometimes she brought me good news as well as bad. One day she said, “There is a clergyman coming to see you, who used to be a great friend of yours, but since your conversion he has been afraid of you. He is coming; you must allow him to preach; he will be converted before long!” Sure enough, my old friend W. B. came as she predicted. He preached, and in due time was converted, and his wife also. Her sayings and doings would fill a book; but who would believe these things?‘

It should be pointed out that Cornwall has a long tradition of village ‘wise women’, an ancient line of pagan folk medicine and healing in the Celtic tradition. This was usually opposed and denounced as witchcraft by the Church, but it seems from the Haslam episode that some wise women were at home with Christianity – and their spirituality at times welcomed by the converted.

“All-Beclouding Hopelessness”: What ‘Prince of Preachers’ Charles Spurgeon Learned from Depression

Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834-1892) hit the headlines young and never left them. He could quote whole sections of the New Testament from memory. He had a library of 10,000 books and had read them all. In his teens he could understand deep theological points that confused many adults. At only 19 years of age, he was invited to pastor a respected Baptist church in London.

Large crowds came to hear him. His biblical prowess was obvious but his style unorthodox, his sermons more like stories. He quoted from the newspapers and took everyday situations, making spiritual points out of them, so that anyone could understand his message. He became a sensation, becoming known as ‘the Prince of Preachers’.

Disaster was to strike, however. In 1856, when he was preaching at the 10,000-seat music hall of the Royal Surrey Gardens, a prankster shouted “Fire!”. In the stampede, 7 people were trampled to death. Spurgeon was devastated. ‘Perhaps never a soul went so near the burning furnace of insanity,‘ he wrote later, ‘yet came away unharmed. ‘From that day on, he knew bouts of dark depression.

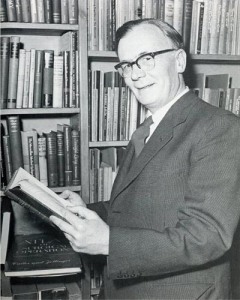

Spurgeon at the height of his ministry

What’s more, he suffered from Bright’s disease, rheumatism and gout, so severe that, in his final years, he was regularly too ill to preach and had to go the South of France to convalesce. Even so, Spurgeon continued to pour himself into God’s work, not least through his magazine, The Sword and the Trowel, and his many books (which are still widely read today). He stood as a bulwark against Higher Criticism, the rationalist theology coming from Germany, which threatened to undermine the true biblical faith.

One fruit of Spurgeon’s battle with depression is that he wrote about it. When a Preacher is Downcast was one sermon, pregnant with his own experience.

‘Knowing by most painful experience what deep depression of spirit means, being visited with it at seasons by no means few or far between, I thought it might be consolatory to some of my brethren if I gave my thoughts on it…

Most of us are in some way or other unsound physically… As to mental maladies, is any man altogether sane? Are we not all a little off balance? These infirmities may be no detriment to a man’s special usefulness. They may even have been imposed upon him by divine wisdom as necessary qualification for his peculiar course of service…Where in body and mind there are predisposing causes to lowness of spirit, it is no marvel if in dark moments the heart succumbs to them.

The preacher’s work has much to try the soul. The loneliness of God’s prophet tends to depression. How often do we feel as if life were completely washed out of us? After pouring out our souls over our congregations, we feel like empty earthen pitchers which a child might break.

In 1858, at the age of 24, he wrote: “My spirits were sunken so low that I could weep by the hour like a child, and yet I knew not what I wept for.” In his ‘Lectures to My Students’, he made this observation:

Causeless depression cannot be reasoned with, nor can David’s harp charm it away by sweet discourses. One would as well fight with the mist as with this shapeless, undefinable, yet all-beclouding hopelessness.

Yet even here he can sound a note of hope: The iron bolt which so mysteriously fastens the door of hope and holds our spirits in gloomy prison, needs a heavenly hand to push it back. It was to this heavenly hand that Spurgeon constantly looked, as we will see in a following post.

John Piper, in a perceptive article on Spurgeon and adversity, sees several contributing factors to Spurgeon’s depression.

Overwork. His friend, missionary David Livingstone, said he did the work of two men every day: running his orphanage (Spurgeons, still a leading charity today) and a church of 4,000 members (the Metropolitan Tabernacle, London); editing a magazine, writing books, answering several hundred letters a week – the list goes on. Spurgeon saw this as a virtue (“If we die early because of excessive labour, there is more of heaven“). Today, many would seriously question his ‘work – life balance’.

Pain and sorrow. He married Susannah in 1856. Their twin sons were born the day after the horrific stampede at a service where he was preaching in 1856, where seven people were trampled to death. So for Spurgeon, even the gift of fatherhood was a mixed blessing. They had no more children. When Susannah was 33, she became an invalid and remained so until she died, 27 years later. Spurgeon himself suffered so badly from gout that he felt he was being bitten by snakes. He was known to say that the pain would be the end of him.

Hostile criticism. Perhaps because he was a larger than life figure and popular, Spurgeon was attacked from all quarters of the Church. In 1857 he wrote: “Down on my knees have I often fallen, with the hot sweat rising from my brow under some fresh slander poured upon me; in an agony of grief my heart has been well-nigh broken.”

Yet it was the trauma of the seven people trampled to death in the Royal Surrey Gardens that broke something in him, at only 22 and newly wed. In his first book, The Saint and His Saviour, he described his agony:

When the storm was over, a kind of stupor of grief ministered a mournful medicine to me. I sought solitude, where I could tell my griefs to flowers and the dew could weep with me. Here my mind lay, like a wreck upon the sand, incapable of its usual motion. I was in a strange land, and a stranger in it. My thoughts, which had been to me a cup of delights, were like pieces of broken glass, the piercing and cutting miseries of my pilgrimage.

In time, Spurgeon learned to rise from this deep pit of ‘shapeless, undefinable, yet all-beclouding hopelessness‘ and make his mark on church and nation. Eventually, he could even see divine providence behind it.

By nature a fighter, Spurgeon initially refused to accept depression. He called it his “worst feature.” “Despondency is not a virtue; I believe it is a vice. I am heartily ashamed of myself for falling into it, but I am sure there is no remedy for it like a holy faith in God.” With the passing years, as bouts of depression continued to lay him low, he came through to various conclusions, which may be of help to anyone who struggles with the ‘all-beclouding hopelessness.’

In an early (1859) sermon, ‘The Sweet Uses of Adversity‘, he writes: Perhaps in your own person you are the continual subject of a sad depression of spirit? and offers some thoughts. These could be seen as the standard Christian answers, even a little pat.

- It may be that God is contending with you that he may show his own power in upholding you (much as the parent of a gifted child delights to see it put through hard questions, because he knows the child can answer them all).

- Perhaps, O tried soul, the Lord is doing this to develop graces in you. Afflictions are often the black mounts in which God sets the jewels of his children’s graces, to make them shine the better.

- God is chiselling you, making you into the image of Christ. None can be like the Man of Sorrow unless they have sorrows too.

We sense two things emerging. First, an undefensive acceptance that bad and painful things happen, and we may never know why. The great preacher who could analyse most things in life and present them in a 3-heading sermon, could not analyse pain and depression.

Second, a more mature response to the issue of depression, born of his experience. In a later sermon, ‘When a Preacher is Downcast‘, he stresses the need for wisdom, recreation, for time spent enjoying nature, and for vacations to maintain a healthy soul. He also brings in the positives of his experience in the dark valleys of depression.

- This depression comes over me whenever the Lord is preparing a larger blessing for my ministry. The cloud is black before it breaks and overshadows before it yields its deluge of mercy.

- Depression has now become to me as a prophet in rough clothing, a John the Baptist heralding the nearer coming of my Lord’s richer blessing. So have far better men than I found it. The scouring of the vessel has fitted it for the Master’s use. Immersion in suffering has preceded the filling of the Holy Ghost. The wilderness is the way to Canaan. The low valley leads to the towering mountain. Defeat prepares for victory. The raven is sent forth before the dove. The darkest hour of the night precedes the day-dawn.

Portraits of German American Pioneers: the Work of Moravian Artist, Johann Haidt

I recently discovered the paintings of a little-known but remarkable artist, who has greatly enriched our understanding of the 18th century Moravian Church through a series of portraits of some of its first-generation members in America.

Johann Valentin Haidt (1700-1780), son of a Danzig jeweller, studied painting at Venice, Rome, Paris, and London, where he finally settled and worked as a watchmaker. He grew weary of the deistic Enlightenment thinking of the day and was drawn to the plainer, more sincere devotion of the Moravians. In 1740, at one of their gatherings, he was profoundly moved. “There was shame, amazement, grief and joy, mixed together, in short, heaven on earth. Therefore I had no more question as to whether I should attach myself to the Brethren.”

Haidt and his family soon moved to the birthplace and European headquarters of Moravianism, at Herrnhut in Germany. It was a time of change in the movement and Haidt hit on a novel idea. He wrote to the founder, Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf, asking permission to paint rather than the usual Moravian missional activities. He felt he could better preserve and proclaim the central message of their faith in paint than in word. So he began painting biblical and spiritual works, while still accepting some secular commissions.

In 1754 Haidt was ordained a deacon in the Moravian Church and was sent to America. A year later he was based at their communitarian colony at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, headquarters of their operations in America. He was sent on missionary journeys to Native Americans from Maryland to New England, but he continued to paint, which among other things brought some income into the movement. He also taught painting. Sarudy’s blog offers fascinating details.

It is his portraits of members of the Bethlehem colony, though, that are Haidt’s lasting legacy. They put a human face to a story that can otherwise be just names, events and places. Sarudy reproduces several from the archives at Bethlehem and Herrnhut. An image search online produces several more. Thanks to the Germanic efficiency of Moravian record keeping, journaling and letter writing, together with their tradition of recording the final reminiscences of members on their deathbeds, we have the precious chance to match a portrait with biographical details. Two examples are the sitters reproduced in this post.

Anna Maria Lawatsch (1712-1760) is pictured above in the plain, even austere dress of a married Moravian woman, not least the Mittel-European two-layer headdress or Haube. The only colourful aspect of women’s clothing was their ribbons: red for young girls, pink for eligible maidens, blue for wives, and white for widows. Anna Maria was an ‘Eldress’, overseer of the community houses for single women and married couples, in several colonies, including Herrnhut. The link quotes extensively from her writings. On her tombstone at Bethlehem the ‘virtue name’ Demuth (humility) is added to her name.

Christian Protten (1716-1769) was the son of a Dutch sailor and an African princess of the Ga tribe. His mixed race features and hair are clear in the portrait. In Denmark he met Zinzendorf and went to Herrnhut. The link reveals some racial prejudice towards him there (he was ‘a wild African’), so he was sent on mission to Ghana; his strained relationship with Zinzendorf, including seasons of ‘shunning’ and a time of separation from his mulatto wife; and final reconciliation and the founding of the first Christian grammar school in the Ga tribal lands of Ghana.

Signs and Wonders: the Remarkable Ministry of Maria Woodworth Etter

Maria Woodworth Etter (1844-1924) was a true pioneer in the history of “signs and wonders” in the church. A diminutive, uneducated woman from the backwoods of Ohio, she was rough-speaking and marked by suffering (five of her six children died). For more details, see this useful blog post by Shawn Stevens.

Even so, she felt a call from God at age 35 to proclaim the gospel. It was a day where women could not vote, let alone preach. So she asked God to qualify her. She records: The power of the Holy Ghost came down like a cloud. I was covered and wrapped in it. I was baptised with the Holy Ghost and fire, with power which has never left me. [‘A Diary of Signs and Wonders’]

She began touring with a gospel tent. This was well known in America, but Maria’s meetings were different. People fell to the ground and lay there for hours. Some saw visions of heaven, which they reported to the audience. Others spoke in tongues. Angelic singing was heard, even by journalists.

God used her most strikingly, though, in healing. People travelled hundreds of miles to be prayed for by her. She believed and taught that every need was already supplied in Christ’s atonement. She got people to lift their hands and praise God from the heart; then with authority she would command the sickness to go. In her various books and in press reports of the day, there are ample testimonies of the crippled running, cancers disappearing, decayed organs restored, the deaf hearing, and the mentally ill recovering.

What makes Maria Woodworth Etter stand out is the magnitude of the healings that took place in her campaigns. Many of these read like the Book of Acts. For this alone she has been called “perhaps the greatest woman evangelist in the history of the Church”. Here are a few examples, taken from her book A Diary of Signs and Wonders (1916, reissued by Harrison House).

Regenerated tissues

‘A sister had met with an accident five years before. Her hip [muscles] had wasted away and for three years she had not left her bed. I saw she was in a terrible condition, but I knew there is nothing too hard for the Lord. I told her to put her trust in Him, then I prayed and she arose, perfectly healed of all her diseases, and went shouting around the house.’

Some sickness linked to demonic oppression

‘A little girl was carried into the meeting [at Springfield, Illinois, c.1884], as helpless as a baby. She had spinal meningitis, was paralysed all over, her brain was impaired, her head dropped on to her chest, and she had no use of her back and limbs. She had been so for six months, and for four months had only eaten nothing but drunk a little milk.

‘I laid hands on her and commanded the unclean spirits to come out of her. In five minutes she could sit up straight and lift her hands above her head. Five minutes more and she could talk and stand up… The next morning she was the first one up, running from house to house telling what God had done for her.’

Miraculous healing of multiple diseases

‘[A man of 64 in Indianapolis] had had piles for 30 years. He had had them cut and burned off four times; then cancer commenced. He got so bad that he had to sit on an inflated ring, and his wife had to flush his bowels twice a day, using a long syringe and tube and 2 quarts of water. Then he would bleed and it was so offensive that she could hardly do it.

‘The bowel was all gone on the left side for ten inches up; the backbone was exposed, having no flesh on it. He also had rheumatism… God converted and healed him all at once, in less than 15 minutes. He was baptised with the Holy Ghost and is now one of God’s little ones. There is nothing too hard for our God!‘

Healing as a pointer to God’s heart

‘[In Muscatine, Iowa], a lady came to the meeting suffering greatly. Eight months before, she had fallen down a flight of steps; her arm and wrist had been broken and her fingers crushed. The arm and hand were very swollen and inflamed. Doctors gave her no hope of ever being able to use the arm or hand.

‘When we prayed for her, the people crowded around to see what would happen. When they saw her begin to move her fingers and hand, and saw the swelling going down, and saw her stretch out her arm, then clap her hands shouting “I am healed!”, they could scarcely believe their eyes. Strong men, who were not believers, wept and said “Surely God is here!”

Her work did not go unopposed. Medical practitioners sought to get her committed as insane, but the press generally defended her. The manifest healings spoke eloquently of God’s grace working through her. We sense something of the personal cost in this report from the St Louis Globe of 1890:

The meeting was one of the most disorderly that has ever been witnessed under the tent, for no sooner would someone throw up his or her hands in a religious ‘trance,’ than the crowd would stand up on the seats, push forward, and do everything but literally climb over each other to see the person. Mrs. Woodworth’s face had a harassed or troubled look, but she still possessed the same pleasant welcoming smile which she always wears; and she walked up and down the platform making the same graceful curving gestures which many claim to be her method of hypnotizing her followers.

On account of the many unusual things she had experienced, and the evident Holy Spirit power in her gatherings, Maria was welcomed by early Pentecostals as a forerunner of their own movement. She worked alongside several pioneers like F F Boswell and John G Lake, who called her “Mother Etter”.

They Called Him Crazy: the Eccentric but Fruitful Revivalist Preacher, Lorenzo Dow

Lorenzo Dow (1777-1834), from Connecticut, USA, took eccentricity to a new level. From childhood he knew sweeps of emotion beyond his fellows, higher highs and deeper lows. His conversion experience was unusually dramatic too: in a dream, he was carried off to hell by a demon, and cried to God that he deserved it – but begged for mercy. He knew amazing peace and joy and woke up loving God.

At 21, he was accepted as a circuit preacher by the Methodists. Later he was an independent evangelist. He quickly gained a reputation, both for his appearance and his methods. Lorenzo usually had just the clothes he stood up in, which he wore until they were so unsightly that some person in the audience would donate a replacement – which might not be the right size. He had a beard down to his chest and never combed it. He didn’t always wash. After his death, one obituary said: Who will forget his orangutan features, his outlandish clothes, the beard that swept his aged breast, or the piping treble voice in which he preached the Gospel of the Kingdom.

He and his wife Peggy embraced poverty for the gospel’s sake. They would often sleep rough in the woods. Peggy wrote a journal of these times, later publicised as Vicissitudes in the Wilderness (available online here).

Dow’s preaching mannerisms were a revelation. A generation before, the great open-air preacher George Whitefield was passionate but serious and measured. Lorenzo Dow shouted, wept, begged, jumped on tables, argued with imaginary opponents, and challenged people’s complacent beliefs. He told stories and jokes. On one occasion, mid-sermon, he snapped his Bible shut and jumped out of the window on to his waiting horse and rode off. He loved to turn up at a public event, go to the stage (uninvited) and announce loudly that he would preach on that spot in one year’s time. It is recorded that he could hold an audience of 10,000 spellbound.

He gained the nickname “Crazy Dow” and happily accepted it. Lorenzo himself wrote a retrospective account of his many experiences, The Dealings of God, Man, and the Devil (available online here). In it he gave to the English language the proverb, “damned if you do and damned if you don’t.”

An oft-quoted episode took place in Westminster, Maryland, and he repeated it elsewhere. Seeing a boy with a trumpet, he enlisted his help. After the start of a service in a meeting hall, the lad was to climb an adjoining tree and wait for a signal. Inside, Dow preached a “fire and brimstone” message. In a great crescendo he cried: ‘If Gabriel were to blow his trumpet announcing the day of Judgment is at hand, would you be ready?’ It was the signal. The boy blew the trumpet! People screamed and rushed to the front to seek mercy and make peace with God. The boy made a quick getaway! This and other anecdotes can be found here.

His engagement to Peggy was suitably unusual. He would marry her, he said, but “if you should stand in my way in the service of the gospel, I will pray to God to remove you!” Stout-hearted Peggy said yes nevertheless and they married in 1804. She accompanied him on many of his travels, which were long and arduous. They would camp in the woods without a tent, hearing wolves but trusting God. This they did out of love for the hundreds of settlers, born and bred in the wilderness, and now adult, who had never seen a preacher.

One record exists of Dow arriving at a village in Alabama: his pantaloons were worn through, and for several hundred miles he had ridden without a cloak, for he had sold it. He was barefoot and his umbrella was held by just three spokes. Small wonder that Peggy entitled her autobiography Vicissitudes in the Wilderness. When Peggy died, Lorenzo married Lucy, who was every bit as feisty as he: at their wedding she promised “to be a thorn in his flesh and a sword in his side”!

Despite their grinding poverty, however, Dow made a point of refusing lavish gifts from well-wishers, accepting only the bare essentials. Such a lifestyle took a toll on his health. He had asthma and malaria and, like the great Methodist circuit preacher Francis Asbury, could not stand for a whole preaching but had to lean on something. He had a special jerkin made with several belts, to enable him still to sit erect on a horse; after that he used a horse and cart.

Dow was a phenomenon, a source of entertainment as well as awe. Many a child was christened Lorenzo in his honour. But he also provoked opposition, especially in southern states, where he opposed slavery. He was sometimes pelted with stones, eggs, and rotten vegetables. That never stopped him; he simply walked to the next town and gave the same sermon again! At Jacksonborough, Georgia, he was abused and attacked so badly that, on leaving, he “shook off the dust from his feet” [Matthew 10:14] and cursed the place. Within a few years, all that was left of Jacksonborough was the home of his hosts – the rest had been abandoned and fallen into ruin.

In all, Dow made three trips to Britain, where he longed to preach the gospel to Roman Catholics. He was received as something of a curiosity but his preaching was respected everywhere. He introduced a group of Methodists to the American-style “camp meeting“, where revivalist preachers spoke to crowds in giant open-air congregations, which might last 3 days. As a result, Hugh Bourne and the Primitive Methodists began holding them in England.

The editor of his journal continued: “His eccentric dress and style of preaching attracted great attention, while his shrewdness, and quick discernment of character gave him no considerable influence over the multitudes that attended his ministry. Who has not heard of Lorenzo Dow? He was one of the most remarkable men of his age for his zeal and labor in the cause of religion. It is probable that more persons have heard the Gospel from his lips, than any other individual since the days of Whitefield.”

The Wounded Healer: Bible Scholar J B Phillips’ Mental Health Struggles

J.B. (John Bertram) Phillips (1906-1982) is remembered today chiefly for his paraphrase of the New Testament: The New Testament in Modern English. A canon in the Anglican church, he realised that people did not easily understand the English of the Authorised Version, so he began his own, readable version in the air-raid shelters of London during the Blitz of 1941. It was described by one reviewer as “making St. Paul sound as contemporary as the preacher down the street” and “transmitting freshness and life across the centuries”.

What is less well known is that Phillips suffered mental affliction for many years – and wrote about it. It seems his father was never satisfied with anything John did as he was growing up. This turned him into a perfectionist. Yet, because he was always falling short of his own standards, he constantly struggled with self-recrimination and a fear of failure. He could not bear any criticism.

Phillips received hours of counselling, but to little avail. Throughout his life, even as he helped others with their spiritual doubts, he knew mental troubles of his own (including ‘visitations’ from C S Lewis, who was already dead). Yet he never let the fears and guilt overcome him. He worked hard, writing, counselling and addressing large audiences.

One fruit of his struggles is that Phillips thought through the dark things of human life, prayed, then wrote about them. Here is how he describes his battles:

“I can with difficulty endure the days, but I frankly dread the nights. The second part of almost every night of my life is shot through with such mental pain, fear and horror that I frequently have to wake myself up in order to restore some sort of balance.”

His writings offer a rational, sensible account of the Christian faith, devoid of frills and triumphalism. It is no surprise that his biography, by his widow Vera and Edwin Robertson, is called The Wounded Healer – because this is what Phillips became. They write:

“While he was ministering to others he was himself powerfully afflicted by dark thoughts and mental pains. He knew anxiety and depression from which there was only temporary release. And while he never lost his faith in God, he never ceased to struggle against mental pain.”

Phillips won through, in part, by choosing to be a giver. Through his books and his wide correspondence, he ministered to people going through their own darkness. At times, the most helpful thing he could offer was his own experience. In one letter to a fellow struggler he wrote:

“As far as you can, and God knows how difficult this is, try to relax in and upon Him. As far as my experience goes, to get even a breath of God’s peace in the midst of pain is infinitely worth having.”

Perhaps, in the final resort, Phillips’ experience was akin to his paraphrase of 1 Peter 5:7 : “You can throw the whole weight of your anxieties upon him, for you are his personal concern.”

Some Anecdotes about John Wesley, the Methodist Pioneer

I have been reading, with great interest, Anecdotes of the Wesleys: illustrative of their character and personal history, published in 1869 by Joseph Beaumont Wakeley. A rather error-strewn typescript is available here.

Anecdotes show the human side of a public figure, their wit, their foibles, their more spontaneous opinions. Which in turn makes them more accessible, as real people like us. So here are a few examples taken from Wakeley’s book, chosen to illustrate various aspects of John Wesley the man.

Commitment

He was once asked by a lady, “Suppose that you knew that you were to die at 12 o’clock to-morrow night, how would you spend the intervening time?”

“How, madam?” he replied. “Why, just as I intend to spend it now. I should preach this night at Gloucester, and again at five to-morrow morning. After that I should ride to Tewkesbury, preach in the afternoon and meet the societies in the evening. I should then repair to friend Martin’s house, who expects to entertain me, converse and pray with the family as usual, retire to my room at ten o’clock, commend myself to my Heavenly Father, lie down to rest and wake up in glory!”

Outspokenness

Mr. Wesley met a gentleman with whom he had some religious conversation, who said to him, ” Mr. Wesley, you preach perfection.” “Not to you,” said Mr. Wesley. “And why not to me?”, he inquired.

He answered, ” Because I should like to preach something else to you, sir.” “Why, what would you preach to me?”

Mr. Wesley replied, “How to escape the damnation of hell.”

Quick Thinking

At a certain time John Wesley was going along a narrow street, when a rude, low-bred fellow, who had no regard for virtue, station, or gray hairs, ran into him and tried to knock him down, saying, in an impudent manner, “I never turn

aside for a fool.” Mr. Wesley, stepping aside, said, “I always do,” and the fool passed on.

Good Company

[Dr Samuel Johnson, the famous wit, essayist and dictionary compiler, invited Wesley for a meal and conversation.] Dr. Johnson conformed to Mr. Wesley’s hours, and appointed two o’clock. The dinner, however, was not ready till three. They conversed till that time. Mr. Wesley had set apart two hours to spend with his learned host. In consequence of this he rose up as soon as dinner was ended and departed. The Doctor was extremely disappointed, and could not conceal his mortification. Mrs. Hall said, ” Why, Doctor, my brother has been with you two hours.” He replied, ” Two hours, madam? I could talk all day, and all night too, with your brother.”

This anecdote illustrates John Wesley’s agreeable companionship, his living by rule, and his redemption of time. James Boswell, the biographer of Johnson, says the Doctor observed to him, “John Wesley’s conversation is good, but he is never at leisure. He is always obliged to go at a certain hour. This is very disagreeable to a man who

loves to fold his legs and have his talk out, as I do.”

Principled Giving

Wesley published a Concise History of England, and made two hundred pounds by the sale of that work. He said to Thomas Olivers [editor of the Wesleyan Arminian Magazine from 1775 to 1789], as he informed him of his profits, “But as life is uncertain, I will take care to dispose of it before the end of the week.” Which he accordingly did.

I anticipate more of these anecdotes to follow.

One aspect of researching a