Prepare to Meet Thy Dome? Some Mediaeval Christian Attitudes to Baldness – and its Treatment

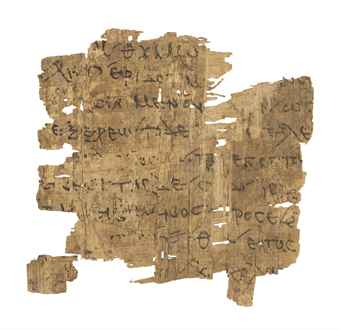

Synesius of Cyrene (died AD 414), was a North African aristocrat and a Neo-Platonist philosopher. He married a Christian woman and embraced her faith, in time becoming bishop of Ptolemais (in modern Libya). He enjoyed debate and, it appears, humour. In the latter vein is his short essay entitled Eulogy of Baldness. Aptly, a eulogy is a speech in praise, typically of one now departed!

He bills it as a riposte to Dio Chrysostom (c. AD 40-115), a Greek orator, philosopher and historian who led a colourful life in the highest circles of Imperial Rome. He had produced an Encomium on Hair. An encomium was a celebratory speech. Here we read: After rising in the morning and praying to the gods, as is my custom, I attended to my hair. I happened to be in poor health at the time, and it had been too long neglected. Most of it had become knotted and entangled, like that which hangs about a sheep’s legs, but much coarser than this, for it is tangled with fine hairs.

What had led Dio to embrace grooming? Consideration of the importance of hair to human beauty and dignity. Homer rarely mentions anyone’s eyes (except Agamemnon’s), he reflects, while Achilles, Odysseus, Menelaus and more are specifically praised for their hair. Dio also considers those around him who love beauty and give their hair great importance, and who not merely give it serious attention but even keep a sort of reed in the hair itself, with which they comb it when they are at leisure… They think much more of keeping their hair clean than of sleeping agreeably.

Synesius admits the Encomium is “so brilliant a work that the bald man, in the face of its arguments, must be covered with shame.” Even so, he jumps to the defence of the follicly challenged. His Eulogy is wonderfully tongue-in-cheek. Besides taking issue with Dio’s reading of Homer, Synesius makes points like these:

Wild animals are hairy; bald animals are intelligent

The most intelligent of all people, the philosophers, are all bald

A sphere is a perfect, even divine form

The glimmer of a bald head is a source of light

He includes a riotous account of a battle between Alexander the Great and Darius of Persia, where the Persians found they could seize a Greek by his long hair and beard and dispatch him with ease. Alexander was forced to retreat and set the barbers loose on his troops. Thereafter, the Persians, the campaign no longer proceeding according to their hopes, as there was no longer anything to hold on to, were condemned to struggle in armour against much superior adversaries.

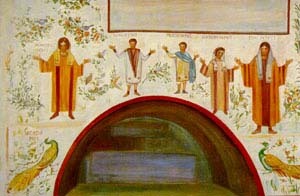

Quite where the tonsure, the shaved bald patch of monks, fitted into this scenario, I have yet to find out. ‘All things to all men’?

Fast forward to the 12th century and we find no less than Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), abbess, writer, composer, philosopher and general polymath, with things to say about baldness. In her On Natural Philosophy and Medicine she sees a link between male head hair and facial hair and male fertility – one of the first to do so. And as for male pattern baldness, she even lists a cure :

Take bear fat, a small quantity of ashes from wheat straw or from winter wheat straw, mix this together and anoint the entire head with it, especially those areas on the head where the hair is beginning to fall out. Afterwards, he should not wash this ointment off for a long while… Let him repeat this often and not wash his head. For the warmth of bear fat has the property of causing much hair to grow… When these ingredients are mixed as described, they will hold a person’s hair for a long time so that it does not fall out.

No doubt the sheer smell and unpleasantness would also have appealed to the contemporary love of penance and punishing the flesh?