Two 7th Century Apostles: Aidan in Britain and Alopen in China Compared

In AD 635, two men were sent out on apostolic missions and, in the face of great dangers, broke through with the gospel in hitherto unreached lands. Aidan was a fiery Irishman, Alopen a refined Persian. Both were monks, both gifted communicators. Entirely independently, both were commissioned and sent to start churches: one at the North-West frontier of civilisation, the other in the far East. Aidan became the Apostle of northern England, Alopen the Apostle to China. Despite their extraordinary linked destiny, they never met or even knew of each other.

Britain at the turn of the 600s was a battleground of warring tribal kingdoms, most of them pagan. A Christian prince named Oswald was sent to the Celtic monastery on the Scottish island of Iona for his own safety. In 634 he felt ready to deliver his kingdom, Northumbria, in the north of England. He defeated the invaders and was crowned king.

One of his first acts was to ask Iona to send someone to convert his pagan subjects. An envoy was sent but returned saying that the Northumbrians were obstinate barbarians, beyond redemption! At this, an Irish monk named Aidan spoke up: it was foolish to expect pagans to accept the strict rules of a Celtic monastery – they must be met on their own level, with grace and humility. For this, Aidan himself was appointed for the apostolic mission to re-evangelise the north of England. It was AD 635.

He established his base on Lindisfarne, an island off the east coast, which became known as Holy Island. Why an island? Because road travel was dangerous because of robbers, and much of the business of life was done by sea. From here teams went out with the gospel, planting churches and establishing centres at Melrose, Jarrow and Whitby. By the time he died in 651, Northumbria was almost wholly evangelised.

Aidan succeeded by developing key relationships with those who helped to expand the work, and by wise and creative planning. He didn’t do all the work himself – at first, he couldn’t even speak the language but needed interpreters. He appointed and trusted many workers. Other noted Celtic saints, Hild (or Hilda), Chad and Cuthbert, built up important ministries under his covering.

But Aidan was a communicator. He could empathise. Any gifts he received from the wealthy, he gave to the poor. This included a fine stallion given to him by the king. The king was furious, but Aidan replied: “Is the son of a mare more important to you than a son of God?” The humbled king knelt and asked forgiveness.

Aidan’s primary witness was through the genuineness of his life. He refused personal gain, showed no partiality (rebuking kings when they needed it), and practised rigorous self-denial. If the king came to Lindisfarne, he had to eat the same food as the monks and beggars. Aidan’s approach was “Do as I do”, not “Do as I say”, and because his life was open to all, people gladly followed and the Church was built.

ALOPEN: APOSTLE OF THE EAST

In ancient times, China was better known in the West than you might suppose. For centuries a trade route called the Silk Road had linked China with Persia and the West. Arab and Persian merchants settled in China, and Chinese envoys reached ancient Rome. But by the 5th and 6th centuries, tribal wars had shut the Silk Road and made China a closed empire.

The arrival of the T’ang Dynasty (AD 618-877) changed all this. The Chinese army crushed the rebels and a golden age of Chinese culture began. The capital, Chang-an (modern Xi-an), was the largest walled city ever built, with two million inhabitants. The reopening of the Silk Road in 632 brought a new cosmopolitan flavour. The Emperor, T’ai Tsung (known today as Taizong), tolerated all religions and encouraged the discussion of foreign ideas.

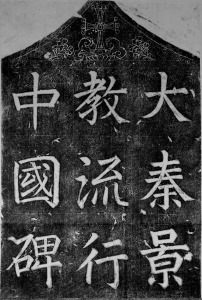

The Church saw its opportunity and took it. In 635, the Assyrian archbishop Yeshuyab sent an apostolic team, led by a learned and wise monk named Alopen. They accompanied a traders’ camel train and arrived at Chang-an.

Alopen had done his homework. He knew the very formal Chinese culture and the need to avoid open war with the Buddhists. So for three years, he and Chinese converts worked on the first Christian book in the Chinese language: The Sutra of Jesus Messiah. A sutra was the way Buddhists presented their teachings, as a series of discourses. Alopen was playing them at their own game.

Much reads strangely to Western ears: Jesus is “the Heaven-Honoured One”, the “Master of the Victorious Law”, who has sent “the Pure Breeze” (the Holy Spirit) from “our Three-One”. But the Emperor was pleased with what he read and in 638 made a decree: Alopen’s religion was “wonderful, spontaneous, producing perception and establishing essentials for the salvation of creatures and the benefit of man“. The Emperor commanded that a Christian religious centre be built from public funds in the Western merchants’ quarter of the city.

From this base, with a core of just 21 Christians, the gospel spread out into the land. Four regional centres were built and by the time of the next Emperor, Kuo Tsung, there were churches in ten provinces. Alopen was made bishop (or in the quaint Chinese, “Spiritual Lord, Protector of the Empire”) and the Church was able to put down firm roots in China – which it would need when persecution was unleashed by Empress Wu in 690.

The New Testament says that the Church is built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets – Christ Jesus Himself being the cornerstone (Ephesians 2:19-20). By their labours, endurance, anointing and above all love, they become fathers to the churches, as Paul, Peter and the others did in the Early Church. It may still be debated whether there are apostles today of the calibre and stamp of Jesus’ Twelve, but the apostolic heart should be something we long to see outpoured more and more, if the Church is regain (and retain) her radicality.

Succession and Commissioning to Leadership in the Early Church

“I am not afraid of an army of lions led by a sheep; I am afraid of an army of sheep led by a lion.” This insightful statement, attributed to Alexander the Great, sums up how crucial it is for any movement to have the right leaders at the helm as they move into their future.

Established denominations have always faced this need, and history has shown inspired choices but also many more appointments based on politics or outward gifting rather than God’s clear choosing (shades of the calling of the shepherd boy David over his more ‘macho’ brothers, 1 Samuel 16:7). The many “new churches” that sprang up in the Jesus Movement of the 1960s and 70s are having to face the issues too. Their leaders are now in their seventies at least. Having turned away from traditional ordination, what models are there for succession? Does any one seem more fruitful than others? And when should a senior pastor initiate the process?

The earliest church communities had been founded by itinerant apostles and their teams. The Acts of the Apostles tells us that, when a need arose, suitably qualified men would be considered before God by the governing corpus of apostles, with prayer and fasting [Acts 13:1-3]. On one occasion we find the drawing of lots [Acts 1:21-26. The apostle’s (or apostles’) selection was ratified by the assembly of the local church, leading to commissioning. There is, however, little practical documentation of how prospective successors and key leaders were trained.

With time, the cultural contexts in which those churches were planted produced a variety of patterns for local leadership, some informed by Jewish models, others by Greco-Roman society. By the end of the 1st century, the pattern that emerged was a threefold, “cascade” structure:

(1) A single pastor-bishop, elected by each community and commissioned by a senior apostolic bishop. He presided over all aspects of the congregation’s life and worship. According to Hippolytus’s ‘Apostolic Traditions’, an episkopos, or senior bishop, should be at least 50 years of age. He was empowered to commission and ordain the second tier, namely:

(2) A shared ministry of leaders known as presbyters / priests / elders, elected by the local church-community, who oversaw the life of the church-community under the leadership of the bishop. These were empowered to commission and ordain the third tier, namely:

(3) Service-oriented ministers, called deacons, who assisted the bishop and the presbyter-elders in both ministry and worship [Acts 6:1-7].

In the first generations of the church, each man in tier 1 was expected to find, train and commission men into tier 2. In time, however, training became more a matter of schools; candidates were sent away from churches to be trained as leaders, rather than being trained within them.

Men in tier 2 were expected to find, train and commission both men and women to serve as deacons.

It is sometimes argued that the Didache (or ‘Teaching of the Twelve Apostles’), dated by most scholars to the late 1st century, disproves such a ‘cascade’. Chapter 15 contains the words: Therefore appoint for yourselves bishops and deacons worthy of the Lord, men who are humble and not avaricious and true and approved, for they too carry out for you the ministry of the prophets and teachers. Some observers see in the words “for yourselves” a more democratic, grass-roots process than a monarchical one. However, the Didache may simply be describing the process we find in Acts 6, where the Jerusalem congregation was told to put forward suitable and respected candidates, whom the apostles then commissioned by the laying on of hands. For further discussion of the Didache on leadership, follow this link.

Sources:

The Ordained Ministry in the Lutheran and the Roman Catholic Church, chapter ‘Ministry in the Second Christian Century, 90 – 210 AD’, which includes a detailed look at Hippolytus’s Didascalia (‘Apostolic Traditions’).

Thomas M. Lindsay, The Church and the Ministry in the Early Centuries.

Since posting this, I have received some helpful insights and comments from David Valentine, via the ‘Patristics for Protestants’ Facebook page. He has kindly given his permission to reproduce them here.

On the tier 1 bishops, for example, the evidence for such mono-episcopacy is far thinner than this article would suggest. As the big promoter of this model, Ignatius of Antioch appears to be the exception rather than the norm – and even he is not inside the first century, as the article implies. The evidence of Clement of Rome, Hermas, Justin and every Roman source (before we even reach non literary evidence such as archaeology) is of a more collegiate, team-based leadership, at least in the imperial capital, until near the end of the second century, when Irenaeus starts providing bishop lists that lack any corroborating evidence in the surviving literature before his time. He may be publishing something accurate, but we lack the evidence to check this and everything else says no, at least for Rome. In Alexandria, working back from Origen’s time (only decades after Irenaeus, and less after Hippolytus) the same pattern seems to be repeated as with Rome: teams of presbyters working together, with a fairly sudden appearance of mono-episcopacy in the first half of the third century, even later than Rome. Smaller cities may have had single leaders earlier, but in the case of Antioch alone (a big city) we have this strong tier 1 model.

Some excellent Anglican studies have suggested that the role of ‘bishop’ was simply that of the relatively rich householders who hosted meetings. It was only good manners that the hosts should preside, unless an apostle or prophet (according to Didache) was present; but this was not simply intended to perpetuate the existing social structure within the Church for all time.

I agree with your observation that the apostles tended to let local churches sort themselves out and be as autonomous as possible, with exceptions as the apostles discerned the need for more direction. Clement of Rome does point to an ongoing respect for the appointments of the apostles, but he can be placed as early as AD 68 – contemporary with the last canonical literature – rather than the ’90’s.

Having waded and brooded for some years on these things, I remain sceptical about what happened after the apostles. We just don’t know if there was a scheme of succession and how it worked. Paul’s own trajectory could even have set a precedent for charismatic leadership appointed in each generation by God.

If the Lord could simply leapfrog the Twelve and start a new stream with a fresh appointment, then Paul’s model of seeking ‘the right hand of fellowship’ to ensure continuity while starting a whole new apostolic stream, could have been perpetuated after him, as it has throughout church history. Wesley, for example, sidestepped Anglican tradition and initiated his own ‘apostolic stream’ by ordaining ministers, and this fresh stream has continued through Methodism and Pentecostalism. Perhaps Paul is the real precedent here.

Best Practice in Church Leadership Succession: the Early Moravians

Church history rightly remembers Nicholas, Count Zinzendorf (1700-1760) as a significant figure. He was a religious and social reformer, founder of the Christian community and mission centre at Herrnhut in Saxony, Germany, from which grew today’s Moravian Church. Under his leadership, missionary teams carried the gospel everywhere, from the Inuit of Labrador to the Zulus of South Africa.

It was a phenomenal achievement. What is far less known is how near the whole movement came to collapse, and how it was rescued and restored. In many ways, we will find here a model of good practice in leadership succession and generational transition in a church. The largely unsung hero was Zinzendorf’s successor, August Spangenberg (1704-92).

He had been a theology lecturer but threw in his lot with the Moravians, aged 29. He became the movement’s theologian, apologist, statesman and corrector – for sixty years! At first, he was an assistant to Zinzendorf, who sent him to Pennsylvania to establish churches, communities and schools – and to address opposition from other denominations. Zinzendorf sought Spangenberg’s mentoring when he was preparing for his own Lutheran ordination. If the count was the visionary of the Moravian movement, Spangenberg was his interpreter and enabler.

However, all was not well in the church. Zinzendorf was more of a visionary than a practical administrator. Under his leadership, the church’s expansion was funded by personal loans. By the 1750s, expenditure was out of control and the church had over-extended itself. This precipitated a spectacular crash in the church’s credit rating and reputation. Detractors used the opportunity to attack them. One major objection was to Zinzendorf’s devotion to the wounds of Jesus, which some saw as too Catholic, others as plain weird.

Zinzendorf died in 1760 with the Moravian church in a precarious position. Spangenberg was recalled from America and, although Moravian leaders saw themselves as equals, Spangenberg was clearly first among them. Under his leadership, the church felt compelled to turn inwards for a season, to address very real issues. They looked at what was central to their call and the way it had hitherto been expressed, and realised that some realignment was necessary.

They took responsibility for the debts and introduced financial controls. They avoided bankruptcy and achieved financial stability.

They apologised for any extra-biblical teaching, admitting that some of the contentious areas had been Zinzendorf’s “private opinions”, which church members were not required to endorse.

They reiterated their commitment to the Bible and to mission.

These reforms worked, much to Spangenberg’s credit. With disasters averted and unhelpful trappings removed, the vibrant church life and gospel endeavour initiated by Zinzendorf flourished. The Moravians concentrated on what they did best: community and mission. Their fruit was remarkable and highly esteemed. While the Great Awakening won souls in ‘Christian’ Britain and America, the Moravians reaped a harvest among the unconverted in other lands. As the 18th century ended, the Moravians had been successfully rehabilitated as the model of a missional church.

Notes:

1. The Moravian Church teaches that it has preserved apostolic succession. In Berlin in 1735, several Moravian Brethren from Herrnhut received episcopal ordination from the two surviving bishops of the Unitas Fratrum (the Bohemian Brethren or Hussites). They considered it important to preserve the historic episcopate.

2. In their earlier years, the Moravians took literally Acts 1:26, the drawing of lots, to determine the will and guidance of God. Their covenant of 1727 included the stipulation that at any time, there should be 12 elders leading the church, all appointed by ‘the lot’. Thereafter, ‘the lot’ was used to help decide key matters like the election of elders, or whom to send on mission. Once the lot was consulted, the decision was seen as binding, since God’s Spirit had spoken.

The usual method was to place two pieces of paper in a box, one with “The Saviour approves” written on it, the other with “The Saviour does not approve”. After corporate prayer, a member of the elders’ council then pulled out one of these papers.

‘The lot’ came to be mistrusted. Some feared leaders could manipulate the lot by rewording and redrawing it until they got the answer they wanted. Others, influenced by the Enlightenment, suggested that God was too rational to use such a haphazard system and that the lot was just a matter of luck. By 1800 it was no longer being used in the Moravian churches.

For further insights, see Nigel Tomes, After the Founding Fathers; Historical Case Studies.

A Revival in Poland Began with Praying Children

In the early 18th century, a revival took place in middle Europe that has received little attention. It had something most unusual about it: it was a revival among the children.

Lutherans were being increasingly marginalised by the Roman Catholic authorities in Silesia, (the borderlands of Poland and Czech today), but the schoolchildren would not accept this. Some time in 1707, the children of Sprottau (today Szprotawa) started to meet in the field outside the town, two or three times a day, to pray for peace in the land and for freedom of religion. They would read some Psalms, sing hymns and pray. There are reports of them falling on their knees, some even lying prostrate, and repenting of their sins. Then, when the right moment seemed to have come, they would close with a blessing.

The movement spread through the mountain villages of Upper Silesia and into the towns. Not all adults were happy about this, fearing the consequences; some tried locking their children in the house, but they would climb out of the windows! In some villages, Roman Catholic children joined the Lutheran children to pray. Reports began to circulate in local newsletters, spreading ever wider until the news was known in England and Massachusetts. To some it became known as the Kinderbeten (children’s prayer) Movement.

Some adults were drawn to the move of God. They would form a circle around the praying children. In some places, the combined number might reach 300 souls. Magistrates brought pressure to bear to disperse these meetings. One bailiff came with a whip, but when he heard the prayers, he could not use it.

Out of this “children’s revival” grew a movement of renewal that touched the area. In time, it found its centre in the Lutheran Jesuskirche church in Teschen (now Cieszyn), which opened in 1750. Here, so many attended services that hundreds had to stand outside the building. Sunday services began at 8 a.m. and continued through the day, in several languages. In turn, the Teschen church provided some of the original members of Count Zinzendorf’s community and fellowship at Herrnhut, known in the English-speaking world as the Moravians.

God’s Presence in a Children’s Prayer Meeting: an Account from the Ulster Revival of 1859

In a collection of pamphlets at the Bodleian Library in Oxford I came across a short account dating from the remarkable Christian revival of 1859 in Northern Ireland. It is written by an anonymous clergyman and entitled Revival in Belfast, the Meeting of the Wee Ones (Dublin, 1860).

Having heard of a group of children meeting regularly to pray and intercede for God’s work in their lives and His blessing on their land, he went to see for himself. The meeting was held in a large attic on the outskirts of Belfast. This is what he found.

He arrived to find the steps crowded with children, and he helped some of them up to the attic level. A mother who saw him exclaimed: “Oh no, here’s a minister! He’ll stop the wee ones!” But he assured her he had come only to learn. She told him the meeting had been going on every evening for two months, from 7.30 till 10. The minister counted 48 children squatting on the floor, eager and reverent. When one of the candles fell on a boy’s head and singed his hair, there was not a stir, not even a titter; he quietly picked it up and put it back.

At the far end of the loft were benches occupied by 70-80 adults, but it was the children who led. The leader, a lad of 13, prayed with power and conviction: Show us our mountain of sin, so we can feel you are our Saviour from them. Jesus, you can set us free for ever! Loose the bonds, Jesus, our Deliverer! Teach us truth and purity! Search all our thoughts, examine our hearts, show us all the things that are hateful in your sight! Burn out our inmost sins and wicked thoughts, against you and against each other. Burn them out, o pure Jesus, but save us in the burning!

A boy of 12 tried to read from the scriptures but got stuck on the long words, so exhorted instead: Won’t you come to Jesus and be baptised in the Spirit? Oh come away from the devil and come to Jesus! Prepare the way of the Lord! You know you don’t feel free from the devil! Jesus wants to come to you!

And so it continued, the boys speaking one by one in orderly fashion. One needed practical help: his parents could not afford the next week’s rent. The children all got out the pocket money and the need was met.

Then, to the clergyman’s shock, the girls began to pray. A 17 year old prayed fervently for the conversion of her family and for forgiveness for all her ingratitude to God. Then, ‘a small girl of about 10 arose, frail in body and clothed in rags. Trembling with the Lord’s anointing, she raised her hands and proclaimed Jesus crucified for our sins. The power fell instantly. A teenage boy slumped to the floor. Many began to weep. Two or three 12-year-olds lay prostrate on the floor. Cries filled the air: “Mercy! Jesus, can you save me? Help, I’m finished!” Others felt the touch of God’s mercy and sang loud praises, tears streaming down their beaming faces.’

Finally, well past ten o’clock, the gathering ended with a favourite hymn from the Primitive Methodist hymnal, Ye sleeping souls, arise!, and one humbled but inspired clergyman returned to his hotel praising the Lord.

Portraits of German American Pioneers: the Work of Moravian Artist, Johann Haidt

I recently discovered the paintings of a little-known but remarkable artist, who has greatly enriched our understanding of the 18th century Moravian Church through a series of portraits of some of its first-generation members in America.

Johann Valentin Haidt (1700-1780), son of a Danzig jeweller, studied painting at Venice, Rome, Paris, and London, where he finally settled and worked as a watchmaker. He grew weary of the deistic Enlightenment thinking of the day and was drawn to the plainer, more sincere devotion of the Moravians. In 1740, at one of their gatherings, he was profoundly moved. “There was shame, amazement, grief and joy, mixed together, in short, heaven on earth. Therefore I had no more question as to whether I should attach myself to the Brethren.”

Haidt and his family soon moved to the birthplace and European headquarters of Moravianism, at Herrnhut in Germany. It was a time of change in the movement and Haidt hit on a novel idea. He wrote to the founder, Count Nicholas von Zinzendorf, asking permission to paint rather than the usual Moravian missional activities. He felt he could better preserve and proclaim the central message of their faith in paint than in word. So he began painting biblical and spiritual works, while still accepting some secular commissions.

In 1754 Haidt was ordained a deacon in the Moravian Church and was sent to America. A year later he was based at their communitarian colony at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, headquarters of their operations in America. He was sent on missionary journeys to Native Americans from Maryland to New England, but he continued to paint, which among other things brought some income into the movement. He also taught painting. Sarudy’s blog offers fascinating details.

It is his portraits of members of the Bethlehem colony, though, that are Haidt’s lasting legacy. They put a human face to a story that can otherwise be just names, events and places. Sarudy reproduces several from the archives at Bethlehem and Herrnhut. An image search online produces several more. Thanks to the Germanic efficiency of Moravian record keeping, journaling and letter writing, together with their tradition of recording the final reminiscences of members on their deathbeds, we have the precious chance to match a portrait with biographical details. Two examples are the sitters reproduced in this post.

Anna Maria Lawatsch (1712-1760) is pictured above in the plain, even austere dress of a married Moravian woman, not least the Mittel-European two-layer headdress or Haube. The only colourful aspect of women’s clothing was their ribbons: red for young girls, pink for eligible maidens, blue for wives, and white for widows. Anna Maria was an ‘Eldress’, overseer of the community houses for single women and married couples, in several colonies, including Herrnhut. The link quotes extensively from her writings. On her tombstone at Bethlehem the ‘virtue name’ Demuth (humility) is added to her name.

Christian Protten (1716-1769) was the son of a Dutch sailor and an African princess of the Ga tribe. His mixed race features and hair are clear in the portrait. In Denmark he met Zinzendorf and went to Herrnhut. The link reveals some racial prejudice towards him there (he was ‘a wild African’), so he was sent on mission to Ghana; his strained relationship with Zinzendorf, including seasons of ‘shunning’ and a time of separation from his mulatto wife; and final reconciliation and the founding of the first Christian grammar school in the Ga tribal lands of Ghana.

From Desert Sand to Peat Bogs: Mediaeval Monastic Links between Egypt and Ireland

In 2006 in County Tipperary, Ireland, an ancient book was found preserved in a peat bog. Now known as the Faddan More Psalter, it contains manuscripts of the biblical Psalms and has been dated to c.800 AD. What is intriguing, however, is the fact that the cover is of a style not commonly found in Western Europe, being more typical of the Eastern Mediterranean, and in the binding were found pieces of papyrus, also from the Levant (or maybe Sicily).

It is not the only pointer to links between Celtic Christianity and the Coptic monasteries of Egypt. A tantalising reference in a 9th century text mentions “seven monks of Egypt in Disert Uilaig” (on the West coast of Ireland). ‘Disert’ (desert) in various forms is found in place names in Scotland, Wales and Ireland. It was the term used by hermits and monks for their own settlements, originating in the actual wildernesses of Egypt and Palestine and then being accepted in the Latin churches as a generic term for a solitary place where a group of monks or anchorites established themselves.

Does this prove an Irish-Egyptian Christian link in the first millennium? Probably not, but there are further pointers. Before the Roman Empire, Celtic-speaking peoples were settled in much of West and Central Europe. Their trade routes spread further still, over the Alps into Italy and down the Danube to the Levant. Celtic warriors were valued as mercenaries. They fought with Hannibal against Rome, and in the 3rd century BC they supported the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt. Many Celts intermarried with Egyptians and remained by the Nile; the Greek historian Polybios records that their mixed-race children were known as e pigovoi.

There was a known maritime trade route between the eastern Mediterranean and the British Isles since the Bronze Age, because tin from Cornwall was needed for the production of bronze for tools and weapons. Celts were also renowned craftsmen, and items of jewellery have been found in Egyptian tombs that are usually identified as Celtic (though some dispute this).

Early Christian writings are clear that John Cassian (360-435), the noted ascetic and theological writer, made a tour of the monasteries of Palestine and Egypt and brought that spirituality back to the South of Gaul. The monastery he founded at Marseille had a rule of life modelled on the Coptic, and its influence spread northwards. Not far away, on the island of Lérins (Lerinum), off Cannes, St Honoratus founded a monastery c.400 which followed the Egyptian rule until the introduction of the Benedictine rule in the 6th century. It is held by some that St Patrick of Ireland came to Lérins and learned Coptic spirituality and practice, but the detail may be apocryphal. Certainly Patrick quotes from Coptic sources in his Confessio.

In the mid-5th century, the Church was torn by a disagreement over a point of doctrine about the nature of Christ. It is known today as Monophysitism. The monks of Palestine and Egypt were on one side of the debate, the power-holding bishops on the other. When the Council of Chalcedon in 451 ruled for the bishops’ position, many monks chose to flee from what they saw as error, and sought new places for their ‘deserts’. This diaspora may well have led some to the Celtic Christian lands.

Finally, Robert Ritner makes a convincing case for parallels between Irish and Coptic Christian art, sculpture and architecture. Egyptian motifs not known in the Roman Christian traditions of Western Europe are found in Ireland. Examples are:

- the handbell used by mendicant monks, which a Coptic bishop received at his consecration, and which appears on the 8th century Bishop’s Stone in Killadeas, County Fermanagh

- preference for the T-shaped “Tau cross” rather than the Western shepherd’s crook for bishops (though the Latin churches did sometimes use the Tau cross)

- the absence of a mitre on the head of bishops, but instead a crown with a jewel

- the prevalence of Egyptian monastic pioneers, St Antony and Paul of Thebes on early medieval Irish high crosses [I am indebted to Gilbert Markus for pointing out to me that this could just as easily have sprung from Jerome’s Life of Paul, which popularised the life of Antony in the West]

- angels in the Celtic illustrated masterpiece, the Book of Kells (c.800), holding strange sticks with circles on the end, which turn out to be flabella, processional fans used to cool important people in the heat of the eastern Mediterranean, and certainly not in Ireland! The imagery can only have been imported from the Coptic context.

[this revision incorporates additional material provided by several people who read the first version. I am indebted to them, especially Meredith Cutrer and Gilbert Markus.]

‘Feed the Hungry, Clothe the Naked’: The Social Conscience of John Wesley

Wesley giving money to free a debtor husband from prison

One great reason why the rich, in general, have so little sympathy for the poor, is because they so seldom visit them. John Wesley

John Wesley (1703-1791) is rightly honoured as a travelling evangelist, revivalist preacher, theological writer, and pioneer of the Methodist movement. Less well known are his lifelong labours on behalf of justice for the poor and destitute.

As a student at Oxford, he was impacted by Jesus’ call to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, welcome the stranger, care for the sick, and visit those who are in prison (Matt.25:35-40). He would fast regularly, dedicating the money he would otherwise have used for dining – as well as all the money, food, and clothing he could solicit from others – for the poor, whom he would regularly visit. This remained a passion throughout his life. Even at age 80, he trudged the snowy streets of London, begging alms for the poor, making himself ill in the process.

It was this proximity with destitution and misery that moved him from distant sympathy to a visceral bond with suffering humanity – a course he urged on all Christians. After spending three days visiting the sick and others at the abominable Marshalsea paupers’ prison (which he described as “a picture of hell upon earth”), Wesley records in his journal: “I found not one of them unemployed who was able to crawl about the room. So wickedly, devilishly false is that common objection, ‘They are only poor because they are idle.’ If you saw these things with your own eyes, could you lay out money in ornaments or superfluities?”

Marshalsea debtors’ prison, London

Wesley’s asceticism was not designed to save his own soul, but rather so that he might give the more generously to the poor. Throughout his life he was not ashamed to beg for them. From the sale of books and pamphlets during his lifetime he is estimated to have amassed £30,000 which he gave away. In 1785 he formed the Strangers’ Friend Society “instituted for the relief not of our [Methodist] society but poor, sick and friendless strangers”.

He built schools and almshouses, and established free medical dispensaries in London, Bristol and Newcastle. He recognised the injustices which meant that so many were condemned to a life of poverty, speaking of “the many who toil, and labour, and sweat … but struggle with weariness and hunger together“. Once, when asked by a tax official to declare all his silver plate on which he should be paying excise duties, he replied: “Sir. I have two silver teaspoons at London, and two at Bristol. This is all the plate I have at present; and I shall not buy any more while so many around me lack bread.”

Mark Mann writes that ‘out of the Foundry [in Bristol], the early Methodists provided much that a contemporary rescue mission might: food, clothing, shelter, medical care, and even financial support in the form of small loans to those without work wanting to start their own businesses. Wesley also founded a home for poor widows, a home for orphans, and several schools aimed especially at the education of poor children.’

In every town where a large church had been planted, Wesley would always appoint seven or twelve men with the special task of visiting and caring for the poor. And this was not only spiritual help, but also the giving of food, clothing and coal for the winter.

In his extensive diary this heart of compassion often shines through. For example, in 1742 at Newcastle, “I walked down to Sandgate, the poorest and most contemptible part of the town, and began to sing a Psalm. Three or four people came out to see what was the matter, who soon increased to four hundred. They stood and gaped at me in astonishment… [That afternoon,] the hill was covered from top to bottom. I knew only half would be able to hear my voice. After preaching, the poor people pressed around me out of pure love and kindness, and begged me most earnestly to stay with them a few days.”

Destitution polemicised by Wesley’s contemporary, artist William Hogarth

A year later, also near Newcastle, we read: “I had a great desire to visit a village of coal-miners that has always been in the front rank for savage ignorance and wickedness. I felt great compassion for these poor people, the more so because all men seemed to despair of them. I declared to them Him who was ‘bruised for our iniquities’. The poor people came quickly together and gave earnest heed to what I said, despite the wind and snow. As most of them had never claimed any belief in their lives, they were the more ready to cry to God for the free redemption which is in Jesus.” He would subsequently refer to the converts there as “my favourite congregation.”

In his book Good News to the Poor: John Wesley’s Evangelical Economics, Theodore Jennings shows how Wesley’s theology demystifies wealth. In absolute contrast to today’s “prosperity gospel”, he ‘regarded Ananias and Sapphira’s sin (Acts 5:1-11) as akin to the fall of humanity in the Garden of Eden. It was the first test of early church, and exposes the love of money as her primal enemy. Therefore the love of money, even possessing excess money, is an ever-present danger to the Christian.’ In later life, however, Wesley ‘was oft to say that the Methodists had proven exceptional at following the first two parts of his essential teaching on wealth (earn all you can and save all you can) but an utter failure at the third (give all you can).’

Even so, his efforts were not in vain. Of Bolton, Lancashire, where the mob had once tried to lynch him, he wrote in 1749: “My heart was filled with love and my eyes with tears. We were able to walk the streets unmolested, none opening his mouth except to thank and bless us.” He could write of many places: “The streets do not now resound with cursing; the place is no longer filled with drunkenness and uncleanness, fighting and bitterness. Peace and love are there.”

When, many years later, a young preacher visited a poor part of Cornwall, he remarked to a miner what an upright people they seemed to be. “How did it happen?” He asked. The old miner bared his head and said, “There came a man among us. His name was John Wesley.”

The First Christian Social Entrepreneur? Basil’s “New City” in 4th century Caesarea

In popular usage today, the term “entrepreneur” seems to mean little more than someone who started their own business. The term is much wider, however, and history reveals a noble line of social entrepreneurs, many of them Christian.

According to this article, a social entrepreneur ‘is usually a creative individual who questions established norms and their own gifting, spirit and dynamism to enrich society in preference to themselves.’ We’re talking about a blend of philanthropist, visionary, business thinker and ‘go-getter’ – and for a Christian, a strong faith.

Christian social care is as old as Christianity itself, of course. The Bible states that caring for widows and orphans is foundational to godliness (James 1:27). Perhaps the first instance of a more visionary enterprise was Basil the Great‘s Basiliad in 4th century Caesarea.

This was a ground-breaking philanthropic foundation where the poor, the diseased, orphans and the aged could receive food, shelter, and medical care free of charge. It was staffed by monks and nuns who lived out their monastic vocation through a life of service, working with physicians and other lay people.

In his funeral address for Basil, his great friend Gregory, bishop of Nazianzus, said: Go forth a little way from the city, and behold the new city, the storehouse of piety, the common treasury of the wealthy… where disease is regarded in a religious light, and disaster is thought a blessing, and sympathy is put to the test. Oration 43, Available online at www.newadvent.org/fathers)

This ‘New City’ was the culmination of Basil’s social vision, the fruit of a lifetime of effort to develop a more just and humane social order within the region of Caesarea, where he grew up and later served as a priest and a bishop.

In this article, Thomas Heyne writes: ‘It appears that some facility (at least a soup kitchen of sorts) existed in 369. By 372 it had professional medical personnel, and by 373 it was sufficiently complete that he could invite fellow leaders to visit. We know that this “new city” housed lepers, as well as other sick, the travellers, and strangers. It was staffed both by professional physicians, as well as by clergy in the adjoining church (not unlike later Christian hospitals). And we know, based on Gregory’s reference to the “common treasury of the wealthy”, that the poor were financed by donations from the rich.’

This line continued primarily through Christian hospitals, only really broadening to other areas with the coming of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th century. As poverty increased and health deteriorated through the factories, a window of opportunity opened for Christian social entrepreneurs. Suddenly prison reform, schools for poor children, cooperative societies, trustee savings banks and suchlike were big on the agenda, and gifted Christian men and women stood up with vision and application to see them through.