“All-Beclouding Hopelessness”: What ‘Prince of Preachers’ Charles Spurgeon Learned from Depression

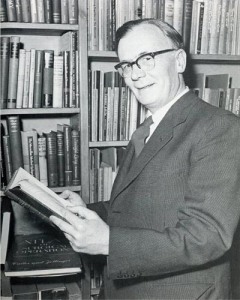

Charles Haddon Spurgeon (1834-1892) hit the headlines young and never left them. He could quote whole sections of the New Testament from memory. He had a library of 10,000 books and had read them all. In his teens he could understand deep theological points that confused many adults. At only 19 years of age, he was invited to pastor a respected Baptist church in London.

Large crowds came to hear him. His biblical prowess was obvious but his style unorthodox, his sermons more like stories. He quoted from the newspapers and took everyday situations, making spiritual points out of them, so that anyone could understand his message. He became a sensation, becoming known as ‘the Prince of Preachers’.

Disaster was to strike, however. In 1856, when he was preaching at the 10,000-seat music hall of the Royal Surrey Gardens, a prankster shouted “Fire!”. In the stampede, 7 people were trampled to death. Spurgeon was devastated. ‘Perhaps never a soul went so near the burning furnace of insanity,‘ he wrote later, ‘yet came away unharmed. ‘From that day on, he knew bouts of dark depression.

Spurgeon at the height of his ministry

What’s more, he suffered from Bright’s disease, rheumatism and gout, so severe that, in his final years, he was regularly too ill to preach and had to go the South of France to convalesce. Even so, Spurgeon continued to pour himself into God’s work, not least through his magazine, The Sword and the Trowel, and his many books (which are still widely read today). He stood as a bulwark against Higher Criticism, the rationalist theology coming from Germany, which threatened to undermine the true biblical faith.

One fruit of Spurgeon’s battle with depression is that he wrote about it. When a Preacher is Downcast was one sermon, pregnant with his own experience.

‘Knowing by most painful experience what deep depression of spirit means, being visited with it at seasons by no means few or far between, I thought it might be consolatory to some of my brethren if I gave my thoughts on it…

Most of us are in some way or other unsound physically… As to mental maladies, is any man altogether sane? Are we not all a little off balance? These infirmities may be no detriment to a man’s special usefulness. They may even have been imposed upon him by divine wisdom as necessary qualification for his peculiar course of service…Where in body and mind there are predisposing causes to lowness of spirit, it is no marvel if in dark moments the heart succumbs to them.

The preacher’s work has much to try the soul. The loneliness of God’s prophet tends to depression. How often do we feel as if life were completely washed out of us? After pouring out our souls over our congregations, we feel like empty earthen pitchers which a child might break.

In 1858, at the age of 24, he wrote: “My spirits were sunken so low that I could weep by the hour like a child, and yet I knew not what I wept for.” In his ‘Lectures to My Students’, he made this observation:

Causeless depression cannot be reasoned with, nor can David’s harp charm it away by sweet discourses. One would as well fight with the mist as with this shapeless, undefinable, yet all-beclouding hopelessness.

Yet even here he can sound a note of hope: The iron bolt which so mysteriously fastens the door of hope and holds our spirits in gloomy prison, needs a heavenly hand to push it back. It was to this heavenly hand that Spurgeon constantly looked, as we will see in a following post.

John Piper, in a perceptive article on Spurgeon and adversity, sees several contributing factors to Spurgeon’s depression.

Overwork. His friend, missionary David Livingstone, said he did the work of two men every day: running his orphanage (Spurgeons, still a leading charity today) and a church of 4,000 members (the Metropolitan Tabernacle, London); editing a magazine, writing books, answering several hundred letters a week – the list goes on. Spurgeon saw this as a virtue (“If we die early because of excessive labour, there is more of heaven“). Today, many would seriously question his ‘work – life balance’.

Pain and sorrow. He married Susannah in 1856. Their twin sons were born the day after the horrific stampede at a service where he was preaching in 1856, where seven people were trampled to death. So for Spurgeon, even the gift of fatherhood was a mixed blessing. They had no more children. When Susannah was 33, she became an invalid and remained so until she died, 27 years later. Spurgeon himself suffered so badly from gout that he felt he was being bitten by snakes. He was known to say that the pain would be the end of him.

Hostile criticism. Perhaps because he was a larger than life figure and popular, Spurgeon was attacked from all quarters of the Church. In 1857 he wrote: “Down on my knees have I often fallen, with the hot sweat rising from my brow under some fresh slander poured upon me; in an agony of grief my heart has been well-nigh broken.”

Yet it was the trauma of the seven people trampled to death in the Royal Surrey Gardens that broke something in him, at only 22 and newly wed. In his first book, The Saint and His Saviour, he described his agony:

When the storm was over, a kind of stupor of grief ministered a mournful medicine to me. I sought solitude, where I could tell my griefs to flowers and the dew could weep with me. Here my mind lay, like a wreck upon the sand, incapable of its usual motion. I was in a strange land, and a stranger in it. My thoughts, which had been to me a cup of delights, were like pieces of broken glass, the piercing and cutting miseries of my pilgrimage.

In time, Spurgeon learned to rise from this deep pit of ‘shapeless, undefinable, yet all-beclouding hopelessness‘ and make his mark on church and nation. Eventually, he could even see divine providence behind it.

By nature a fighter, Spurgeon initially refused to accept depression. He called it his “worst feature.” “Despondency is not a virtue; I believe it is a vice. I am heartily ashamed of myself for falling into it, but I am sure there is no remedy for it like a holy faith in God.” With the passing years, as bouts of depression continued to lay him low, he came through to various conclusions, which may be of help to anyone who struggles with the ‘all-beclouding hopelessness.’

In an early (1859) sermon, ‘The Sweet Uses of Adversity‘, he writes: Perhaps in your own person you are the continual subject of a sad depression of spirit? and offers some thoughts. These could be seen as the standard Christian answers, even a little pat.

- It may be that God is contending with you that he may show his own power in upholding you (much as the parent of a gifted child delights to see it put through hard questions, because he knows the child can answer them all).

- Perhaps, O tried soul, the Lord is doing this to develop graces in you. Afflictions are often the black mounts in which God sets the jewels of his children’s graces, to make them shine the better.

- God is chiselling you, making you into the image of Christ. None can be like the Man of Sorrow unless they have sorrows too.

We sense two things emerging. First, an undefensive acceptance that bad and painful things happen, and we may never know why. The great preacher who could analyse most things in life and present them in a 3-heading sermon, could not analyse pain and depression.

Second, a more mature response to the issue of depression, born of his experience. In a later sermon, ‘When a Preacher is Downcast‘, he stresses the need for wisdom, recreation, for time spent enjoying nature, and for vacations to maintain a healthy soul. He also brings in the positives of his experience in the dark valleys of depression.

- This depression comes over me whenever the Lord is preparing a larger blessing for my ministry. The cloud is black before it breaks and overshadows before it yields its deluge of mercy.

- Depression has now become to me as a prophet in rough clothing, a John the Baptist heralding the nearer coming of my Lord’s richer blessing. So have far better men than I found it. The scouring of the vessel has fitted it for the Master’s use. Immersion in suffering has preceded the filling of the Holy Ghost. The wilderness is the way to Canaan. The low valley leads to the towering mountain. Defeat prepares for victory. The raven is sent forth before the dove. The darkest hour of the night precedes the day-dawn.

The Wounded Healer: Bible Scholar J B Phillips’ Mental Health Struggles

J.B. (John Bertram) Phillips (1906-1982) is remembered today chiefly for his paraphrase of the New Testament: The New Testament in Modern English. A canon in the Anglican church, he realised that people did not easily understand the English of the Authorised Version, so he began his own, readable version in the air-raid shelters of London during the Blitz of 1941. It was described by one reviewer as “making St. Paul sound as contemporary as the preacher down the street” and “transmitting freshness and life across the centuries”.

What is less well known is that Phillips suffered mental affliction for many years – and wrote about it. It seems his father was never satisfied with anything John did as he was growing up. This turned him into a perfectionist. Yet, because he was always falling short of his own standards, he constantly struggled with self-recrimination and a fear of failure. He could not bear any criticism.

Phillips received hours of counselling, but to little avail. Throughout his life, even as he helped others with their spiritual doubts, he knew mental troubles of his own (including ‘visitations’ from C S Lewis, who was already dead). Yet he never let the fears and guilt overcome him. He worked hard, writing, counselling and addressing large audiences.

One fruit of his struggles is that Phillips thought through the dark things of human life, prayed, then wrote about them. Here is how he describes his battles:

“I can with difficulty endure the days, but I frankly dread the nights. The second part of almost every night of my life is shot through with such mental pain, fear and horror that I frequently have to wake myself up in order to restore some sort of balance.”

His writings offer a rational, sensible account of the Christian faith, devoid of frills and triumphalism. It is no surprise that his biography, by his widow Vera and Edwin Robertson, is called The Wounded Healer – because this is what Phillips became. They write:

“While he was ministering to others he was himself powerfully afflicted by dark thoughts and mental pains. He knew anxiety and depression from which there was only temporary release. And while he never lost his faith in God, he never ceased to struggle against mental pain.”

Phillips won through, in part, by choosing to be a giver. Through his books and his wide correspondence, he ministered to people going through their own darkness. At times, the most helpful thing he could offer was his own experience. In one letter to a fellow struggler he wrote:

“As far as you can, and God knows how difficult this is, try to relax in and upon Him. As far as my experience goes, to get even a breath of God’s peace in the midst of pain is infinitely worth having.”

Perhaps, in the final resort, Phillips’ experience was akin to his paraphrase of 1 Peter 5:7 : “You can throw the whole weight of your anxieties upon him, for you are his personal concern.”