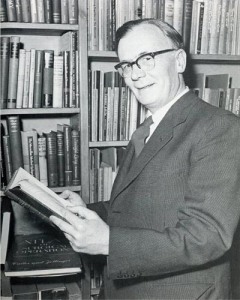

The Wounded Healer: Bible Scholar J B Phillips’ Mental Health Struggles

J.B. (John Bertram) Phillips (1906-1982) is remembered today chiefly for his paraphrase of the New Testament: The New Testament in Modern English. A canon in the Anglican church, he realised that people did not easily understand the English of the Authorised Version, so he began his own, readable version in the air-raid shelters of London during the Blitz of 1941. It was described by one reviewer as “making St. Paul sound as contemporary as the preacher down the street” and “transmitting freshness and life across the centuries”.

What is less well known is that Phillips suffered mental affliction for many years – and wrote about it. It seems his father was never satisfied with anything John did as he was growing up. This turned him into a perfectionist. Yet, because he was always falling short of his own standards, he constantly struggled with self-recrimination and a fear of failure. He could not bear any criticism.

Phillips received hours of counselling, but to little avail. Throughout his life, even as he helped others with their spiritual doubts, he knew mental troubles of his own (including ‘visitations’ from C S Lewis, who was already dead). Yet he never let the fears and guilt overcome him. He worked hard, writing, counselling and addressing large audiences.

One fruit of his struggles is that Phillips thought through the dark things of human life, prayed, then wrote about them. Here is how he describes his battles:

“I can with difficulty endure the days, but I frankly dread the nights. The second part of almost every night of my life is shot through with such mental pain, fear and horror that I frequently have to wake myself up in order to restore some sort of balance.”

His writings offer a rational, sensible account of the Christian faith, devoid of frills and triumphalism. It is no surprise that his biography, by his widow Vera and Edwin Robertson, is called The Wounded Healer – because this is what Phillips became. They write:

“While he was ministering to others he was himself powerfully afflicted by dark thoughts and mental pains. He knew anxiety and depression from which there was only temporary release. And while he never lost his faith in God, he never ceased to struggle against mental pain.”

Phillips won through, in part, by choosing to be a giver. Through his books and his wide correspondence, he ministered to people going through their own darkness. At times, the most helpful thing he could offer was his own experience. In one letter to a fellow struggler he wrote:

“As far as you can, and God knows how difficult this is, try to relax in and upon Him. As far as my experience goes, to get even a breath of God’s peace in the midst of pain is infinitely worth having.”

Perhaps, in the final resort, Phillips’ experience was akin to his paraphrase of 1 Peter 5:7 : “You can throw the whole weight of your anxieties upon him, for you are his personal concern.”

The Evangelist Prince: the Short Life of Kaboo (Samuel Morris)

Prince Kaboo was born in 1873, son of a chief of the Kru tribe in Liberia, Africa. When only in his teens, he was captured in a skirmish with the Grebo tribe, who used him as a pawn in extracting tribute. He was regularly whipped and tortured, and the Kru had to deliver a present every month to keep him alive. If they defaulted, Kaboo would be buried up to the neck, his face smeared with honey, and the ants would eat him alive.

One night, there was a blinding flash of light, the ropes fell off him and a voice said: “Kaboo, flee!” He ran into the jungle, travelling by night and hiding in hollow trees by day, until he reached the capital, Monrovia. Here he found work and was invited to church. Hearing how Saul of Tarsus was converted through a blinding flash of light [the Bible, Acts 9:3-19], Kaboo was astonished at the similarity to his own story, and gave his life to Christ. At his baptism he was given the name Samuel Morris.

After two years, hungry to receive training and to be empowered to preach the gospel, Kaboo was sent to America. He worked his passage, being badly treated by the ship’s crew, but a number turned to the Lord through his witness. Samuel Logan Brengle, an early leader in the Salvation Army, recounts what happened next in his book When the Holy Ghost is Come:

“The brother in New York to whom he came, took him to a meeting the first night he was in the city, and left him there, while he went to fulfil another engagement. When he returned at a late hour, he found a crowd of men at the penitent-form, led there by the simple words of this poor black fellow. He took him to his Sunday-school, and put him up to speak, while he attended to some other matters. When he turned from these affairs that had occupied his attention for only a little while, he found the penitent-form full of teachers and scholars, weeping before the Lord. What the black boy had said he did not know; but he was bowed with wonder and filled with joy, for it was the power of the Holy Spirit.”

He arrived in America aged 18 and was referred to Taylor University, a Christian foundation in Indiana. When the principal asked him what room he would like, Kaboo replied: “Give me the one that no one else wants.”

Kaboo’s simple godliness affected everyone he met. They often heard him calling on God in his room (he called it “talking to my Father”). He took every opportunity to witness to others, but his heart still yearned to return to Liberia with the message of salvation.

It never happened. In 1893, aged 20, he contracted an infection and died. The President of the university made this statement: Samuel Morris was a divinely sent messenger of God to Taylor University. He thought he was coming over here to prepare himself for his mission to his own people; but his coming was to prepare Taylor University for her mission to the whole world. Many of his student contemporaries volunteered for missionary service, to keep alive Kaboo’s vision and to work towards his dream.

A life’s work accomplished in just four years as a Christian! Behind this we can see the meeting of two crucial elements: a clear and powerful divine call and what the university President called Kaboo’s sublime yet simple faith in God.

Taylor University have produced a cartoon format life of Samuel Morris. There is also a short film, A Spirit-Filled Life, available (in poor quality) on YouTube.

A Very Human Leader: Martin Luther Struggled with Depression and Nightmares

On 31st October 1517, the German priest Martin Luther (1483-1546) nailed his 95 ‘Theses’ (subjects for debate) to the door of his church in Wittenberg – the church door in those days doubling up as a community notice board. Luther is rightly remembered as a champion of church reform, who translated the Bible into German, wrote vernacular hymns, and freed the glorious truth of justification by faith from the overburden of empty tradition.

It is also documented that Luther could be touchy, aggressive and opinionated. What is less well known, though, is that doubt and fear of death played a major part in Luther’s psyche throughout his life. He knew phases of dark depression. Particularly in later life, with all his triumphs behind him, he experienced seasons of terror that God had utterly forgotten him and abandoned him to hell. His prayers and cries were met only with silence. He felt alone in the universe. For more details, read this post by Chris Anderson.

At one point, the crushing doubt about his calling led him to such a deep pit of gloom that he wrote, “For more than a week I was close to the gates of death and hell. I trembled in all my members. Christ was wholly lost. I was shaken by desperation and blasphemy of God.’” He had nightmares, sweats and palpitations. Yet even in such a phase, Luther penned his well-loved hymn, ‘A Mighty Fortress Is Our God.’ It is a peculiar but very human mixture: on the one hand, in all sincerity writing books and hymns in praise of God’s glorious gift of freedom in Jesus Christ, but on the other suffering haunting reproach, guilt, condemnation and cosmic fear.

One thing that brought him relief was music. It brought solace and comfort, and when joined with sacred text, it could carry living truth to the heart. To the devils, he wrote, music is distasteful and insufferable. For more on this subject, read Ryan Griffith’s piece here.

Richard Marius, in his study of Luther, offers a very telling image: ” For Luther, Christ was like a campfire projecting a circle of light against the vast dark of earthly life. Whenever the darkness threatened to encroach upon that illuminated ground, Luther flung more of his volatile ink onto the fire, causing it to flame up again in his own heart, and keeping the darkness at bay.”

Portrait of Luther by Lucas Cranach the Elder

So Luther the great champion of doctrinal reform becomes Luther the troubled human being, one of us, someone we can relate to when we hit the rocks of life or hang on cliffs of horrible despair. If he found a way through, then we can surely learn from it and find hope.

The answer that Luther found was to allow tribulation to drive him to prayer and Scripture and above all, to God’s promises. ‘God has need of this: that we consider him faithful in his promises [Heb. 10:23], and patiently persist in this belief.’ [The Babylonian Captivity of the Church] Luther concluded that God uses the assaults of doubt to strip us of self-assurance. In other words, we are unable to wholly grasp the promise of God and our salvation, which saves us from the danger of placing our confidence in ourselves and our own understanding.

In this life, God does not lift the Christian out of human nature, nor does he reveal himself beyond any shadow of doubt. Even to discover God’s saving grace does not necessarily mean escaping spiritual conflict and ‘desert’ experiences. Rowland Croucher writes: ‘As odd as it seems, doubt serves to protect us from ourselves. When we can’t trust our capacity for faith, we have to go back to trusting God and only God. Doubt serves another purpose in the life of faith. If we’re willing to put the energy and effort into the struggle, rather than just walk away, it can serve to keep us engaged with God.’